This is part 2 of my mini-series on women who fought for their rights without waiting for young men’s support, a timely reminder as Gen Z men drift towards Trump and women’s rights hang in the balance. Head here for my full take on why young men’s rightward turn shouldn’t derail the urgent fight for women’s and trans rights. Meanwhile, enjoy this bonkers story about a persistent woman, a nervous university dean and some very rowdy young men.

Elizabeth Blackwell was born in England in 1821; her father, a sugar refiner, moved the family to America in 1832.1 Blackwell’s father died when she was 17. Money was tight, and Elizabeth started teaching, one of the few professions open to women. It was fine, but not very exciting.

Then her friend Mary Donaldson developed cancer, and confided to Elizabeth that the shame of being examined nude by male doctors compounded her suffering. “You are fond of study, Elizabeth. You have health, leisure and a cultivated intelligence. Why don’t you devote these qualities to the service of suffering women? Why don’t you study medicine?” Asked Mary.

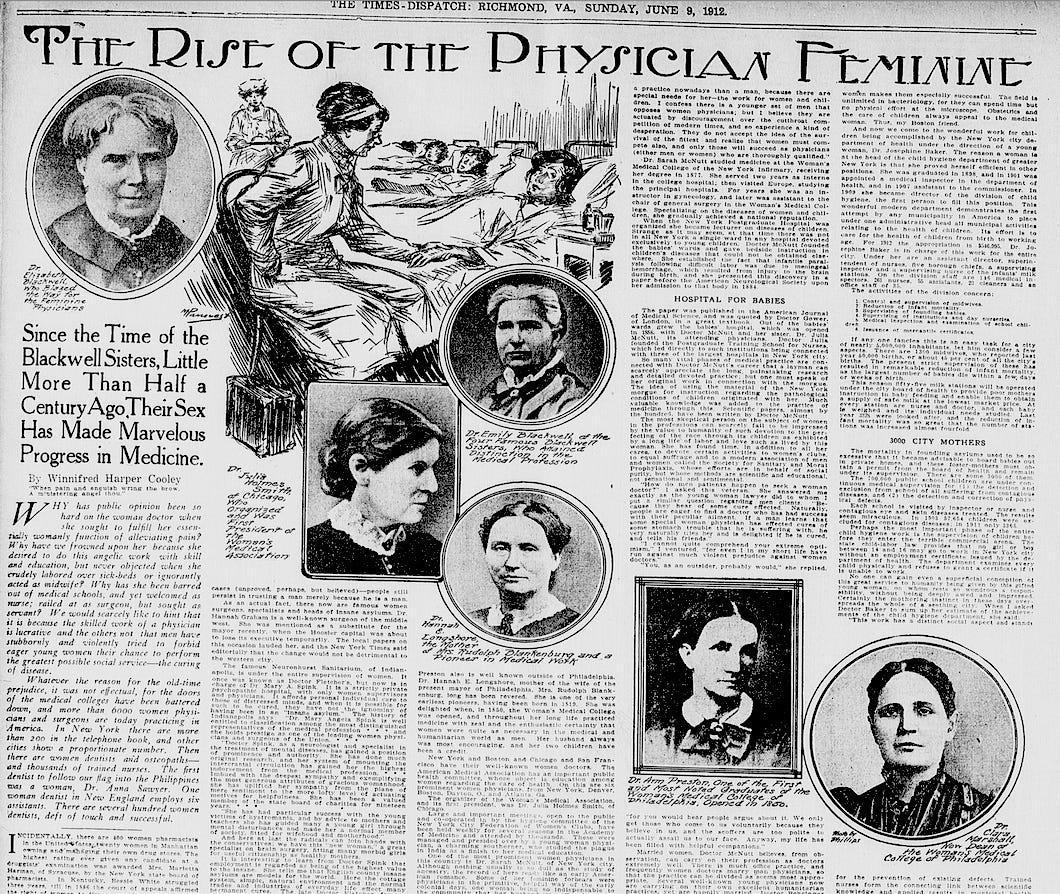

In 1845, this was a crazy idea: no woman had ever graduated from a medical school in the US or Western Europe, and Elizabeth was squeamish about bodily functions anyway. But Mary’s suggestion stuck with her. So, in the summer of 1846, Elizabeth applied to a few medical schools. They all rejected her, which turned her quest into an obsession. “The idea of winning a doctor’s degree gradually assumed the aspect of a great moral struggle,” she wrote in her diary.

Blackwell started studying medical texts and Greek and wrote to physicians all over the US. When one, Dr. Warrington from Philadelphia, expressed admiration for her boldness, she moved to Philadelphia to enlist his support. He wrote her letters of recommendation, and she continued to apply. In all, Blackwell applied to 29 medical schools and was rejected by all.2

As a last resort she tried Geneva Medical College, a small, inexpensive school in upstate New York where medical education required only two years. Stephen Smith, a student at the time, recalled the local saying: “a boy who proved to be unfit for anything else must become a doctor.” The students, mostly sons of local farmers, tradesmen and mechanics were, in Smith’s words, “rude and uncouth country youths whose love of ‘fun’ far exceeded their love of learning.” Fistfights were common, and neighbors tried to have the school declared a public nuisance.

Into this rowdy class walked the dean - “an elderly, courtly, nervous gentleman,” recalled Smith - to tell the class he’d received a request from Dr. Warrington to accept a woman. Unbeknownst to the students, the faculty had already decided to reject Blackwell, but the dean was wary of offending Warrington and decided to let the students vote on it. To guarantee a negative result, he declared that even one ‘nay’ would suffice to reject the application.

But the faculty, Smith wrote, had misjudged their students’ love of mischief. Once the dean made his request and left the room, a stunned silence fell—followed by “a perfect babble of talk, laughter, and cat-calls.” A woman in medical school! What a good joke. The students called a meeting for that night. After florid, uproarious speeches the class rose and voted “Aye” while “waving handkerchiefs, throwing up hats, and all manner of vocal demonstrations.” There was one “Nay,” but after the naysayer’s classmates pounced on him with cries of “cuff him” and “crack his skull,” the poor fellow changed his vote. And thus, Elizabeth Blackwell was admitted into med school.

When Blackwell showed up next fall, townspeople crossed the street to avoid her and wouldn’t rent her a room. Her fellow students, who thought the application had been a prank, were shocked; in her first class Elizabeth was the only one taking notes, while everyone around her sat in stunned silence. Faculty tried to bar her from labs. But Blackwell persevered, and graduated in 1849 at the top of her class. Her sister Emily followed her to medical school a few years later.3

After this Hollywood ending (really, how is this not a movie?) Elizabeth struggled to establish herself; not many patients agreed to see a woman doctor. A devout Christian, she also rejected germ theory, viewed disease as a moral failing, objected to women’s suffrage and dabbled in phrenology, a cousin of eugenics. But her monumental achievement stands. She did not take no for an answer, and a group of young men let her in as a joke. And yet, once she showed up, they accepted her. Another reminder that when women fight for their freedoms, many men will eventually come on board.

I first heard about Blackwell on the Stuff You Should Know podcast

Though not to Geneva, since faculty decided that one woman doctor was quite enough

Great story about not giving up